Yvonne Rainer is one of the most cinematically daring and creative directors of the 20th century. Each of her films feels large and with so much inner life, asking you to engage with them, think, and react, challenging our preconceived notions and bombarding us with visual and theoretical ideas.

Her earliest works were strikingly shot experimental films that may be primarily suited for the already converted to the anti-narrative. However, almost film by film she became more accessible, with the form and themes becoming bolder, larger, and more explosive, leading to utterly wacky laugh riots that could still cut close to society’s core.

Rainer is a dancer and choreographer and this is the tradition of her first two films were born out of, with the New York avant-garde scene accounting for much of the rest. Indeed, similarities to Jonas Mekas, Michael Snow, and others can be detected, with the set from Wavelength even making an appearance. However, she is a very singular filmmaker, easily identified by stream-of-consciousness “storytelling” following thematic threads in all directions, coupled with outplaying Jean-Luc Godard himself when it comes to quotations … Something I had never thought possible.

Her films are doused with political and social theory and frequently meditate on issues related to feminism and left-wing philosophy and practice. She often quotes large sections of essays or speeches, but they are not always what she agrees with herself, even underpaying them with shock, surprise, or dismissal, or posing the sentiments as questions to us, the audience.

If I were to issue a critique it is that the films may suffer if you don’t know the quoted texts, the people who wrote them, what they represented, etc., and that many of her films may as such have been made for a rather niche set of intellectuals. Luckily the heaviness of her work does decrease as her career progressed, and while always balanced by humour and creative energy, the ratio would become adjusted.

It is perhaps telling of my own preferences and taste that it is her final two films, also her most narrative, that remain my favourites. One explosive, the other, well, rather cinematically explosive as well, but also truly human.

In this article, I will go through each of her seven films, each of them worth a viewing, and depending on your taste, interests, and preferences I can see each of them becoming someone’s favourite film by Yvonne Rainer, a testament to her lasting brilliance and the imminent need of rediscovery.

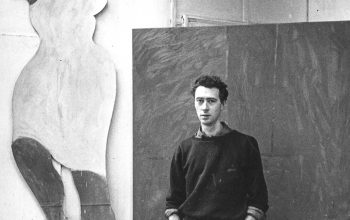

Lives of Performers (1972)

Lives of Performers is an incredibly dynamic work, with striking black-and-white photography and so much playfulness with a cinematic form that it immediately positions her as an artist to watch. It is almost unbelievable to describe it as being set entirely on a single stage, but this is the case in this incredibly ambitious debut.

Narrative structure is turned on its head as Rainer takes apart a play of a love triangle and re-imagines it, using everything from still photographs, to rehearsals to discussions at line readings to both tell the central story and the story of its creation.

I did however find myself struggling a little with the film. In particular, the bold choice to shoot large parts of the play and the rehearsals without audio, a recurring artistic choice of silence we would see in her next two films as well, but with a diminishing length of use. These portions were less engaging, at least for me. While in other eyes it may increase intensity as viewers guess what goes on and what we don’t hear, but to me, they fell a little flat and resulted in the film being my personal least favourite film of Rainer. That said, I could not stop marvelling at the daring creativity behind the choices she made, many of which struck me as genius despite my patience being tested at many points.

It is worth noting that Lives of Performers was a very low-budget production and that there is no sound recorded live. All sound is added afterwards, and rarely used to match what the people on screen are saying. Rather, we hear the actors running lines or discussing ideas as we watch the performances, or simply pictures of the rehearsals. This stylistic choice of the spoken dialogue, be that commentary somewhat related to what we are seeing, or in juxtaposition to it, is a tool Rainer would also continue to develop and make into one of her trademarks, even after the stages would disappear.

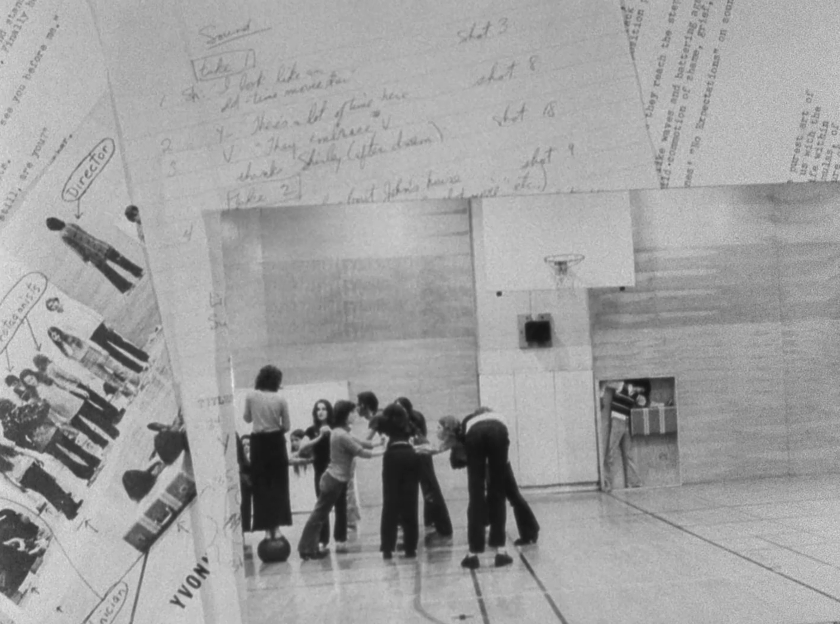

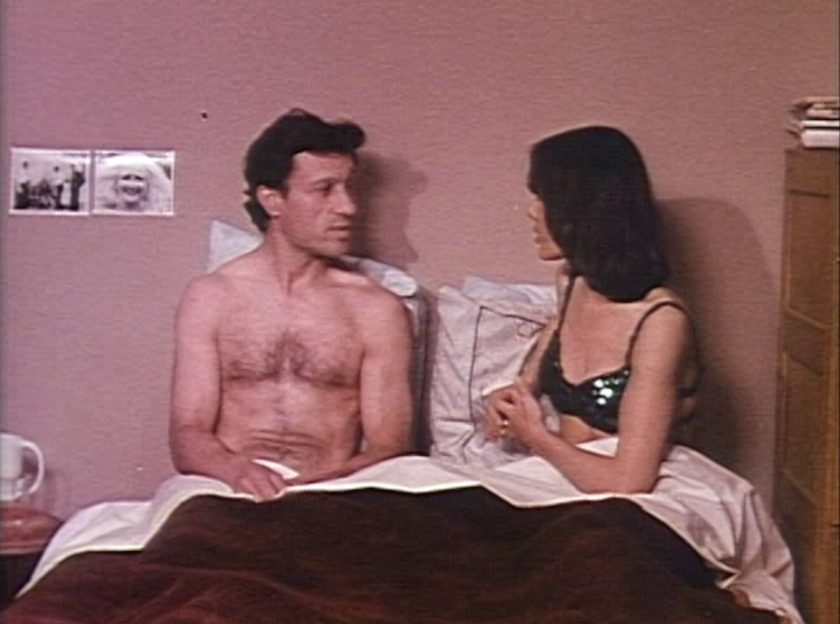

Film About a Woman Who … (1974)

Film About a Woman Who … looks, feels, and breathes like Lives of Performers, but it is a very different beast. While the stage still plays a role, the cinematography is still in striking black and white, there is an overlap of the cast, and all audio is added in after the visual recordings, the film feels so large and free.

At its most basic the film still concerns men, women, their relationships, and “love”, with our central woman becoming upset and not being sure why or how to deal with it. However, from this premise the film goes on to sink its teeth into pretty much everything, riffing on the ideas in all directions, and just opens itself up.

Unlike her debut, Film About a Woman Who … is not contained to the stage, we are in the streets, on the beach, all across New York, and if it was possible, the filmmaking is even more cinematically daring and meta-textual.

It contains my likely favourite section in any Yvonne Rainer film, a scene, or shall I say a sequence, numbered by moments in time, of instances where “something” happens. It is a situation where an issue occurs as a couple is lying in bed. Each action in the sequence is numbered, but the presentation changes. We will see the number, a text explaining what happens or what someone is thinking/saying, and then show them doing just that, but throughout the sequence, we may simply get the number and the text with no images to back it up, or, at its most sparse, just the number, followed by visuals without any guide.

In disjointed creativity, this is a mini-masterpiece, and it is referenced later, partially repeated and the technique is also reused. This kind of free playfulness is both funny and merits further introspection, while humour fills the screen throughout.

There are many moments in this film that remind me, and actually predate, Michael Snow’s So Is This, in its use of text. No, this is not just words on a screen, but it plays a part, as do words printed out and placed on a woman’s face. We can cut from someone speaking to seeing the next lines projected on a screen, vice versa, or both at the same time.

The scenarios that take place in front of us, or behind the scenes, as the film blends readings and quotations over city footage, a memorable set of stagings of family photographs on the beach and situations played out on stage and elsewhere. The free-flowing style that mixes so many different expressions results in the film’s most memorable moments, but as the form is so different, scene after scene, it does run the risk of some sections working for you while others don’t.

For me, the moments in complete silence, such as a scene illustrating a potential threesome where the man removes our lead’s undergarments, revealing her bush, before moving them back up, is an example of a scene that started to test my patience a little. I also felt like some of the use of text, where we for instance see a text from a distance but can still read it, but then cuts in so we can read it more clearly, was an odd and unnecessary artistic choice, though the disjointed usage of text throughout is clearly intentional.

Film About a Woman Who … is a film I can see many heralding as a masterpiece and one I would recommend to everyone interested in experimental cinema. It is also likely to be difficult for many who lean more toward traditional narratives. Luckily for the latter group, as Rainer’s career progressed we would start to get more recognizable narratives.

Kristina Talking Pictures (1976)

Kristina Talking Pictures opens with Rainer speaking to us as “Kristina”, a fictional character, as we span across her current life and loves, and contemplations on her past. While hardly “narrative”, and follows a stream of consciousness zigzag through topics, we are centred on her, making the film easier to follow than its predecessors.

The film marked two significant changes for Rainer. It is not set on a stage, at all, meaning dances/preparations are gone, and more noticeably, it is in colour. There is arguably a trade-off in intelligibility/clarity and visual quality, as the striking b/w photography, complemented by the dramatic contrasts of her sets is now gone. The image quality and composition here remind me of contemporaries, such as Jonas Mekas, and as it is presented in an almost personal essay fashion (though fiction) it suits it very well.

The film is still shot (largely, if not entirely without sound) with the audio not always matching. This is used with incredible prowess in the opening scene, where we see a woman rummaging a room after her lover has left her. We get to see part of his goodbye letter and as she leaves we hear the outside, Kristina getting into a cab, asking it to stop and as soon as it does we see her re-entering the apartment.

We get the occasional silent moment as we see people talk to each other without audio, but unlike her two previous films, these are brief pauses and never feel like they go on too long. They can be amusing, or just a fitting pause, in between back and forth or “narration”.

Kristina Talking Pictures is an interesting case for me as while I was not as wowed by individual moments, I ended up enjoying it more than Rainer’s first two efforts. The reason is simple, the pace is tighter and the style is broadly consistent. It meanders, but with a core, and while Lives of Performers and Film About a Woman Who … jumps between completely different forms, Kristina Talking Pictures has the same atmosphere and presentation throughout, meaning that if you enjoy it from the beginning, the whole experience should be pleasing.

The film also starts a motif or rather alters a motif we were seeing in her previous films, where essays and quotes are read or spoken by characters as if they were talking about their own lives or simply having a conversation. The presentation is fully dry, and especially if you are not familiar with the works quoted may seem almost surreal. They fit the mood and leave room for thought and contemplation, especially as when Rainer quotes a work, and this is something we will see more and more of as her style developed further, it is clear that she does not necessarily agree with it, but wants us to reflect on it.

Journeys From Berlin/1971 (1980)

Journeys From Berlin/1971 is arguably the closest Rainer has gotten to a true essay film, as she meditates on the history of West Germany, its criminalization of communist opposition, and the story of the Baader-Meinhof gang. Once again we find text, both read and on screen, playing a central role. Throughout the film informational text takes us through a narrative of what Rainer presents as authoritarian measures for the democratic country, asking the question of what opposition can do when denied a voice, and along the way taking relevant detours of how such behaviours become reframed as issues of mental health.

While in many ways expansive in scope, even having a bit of an ethereal feeling as large portions of the films are readings and commentary over more general footage of places and spaces, it is also, I would argue her sparsest for that reason. The only real semblance of theatricality is a recurring motif of a woman having a conversation with a man of which we only see the back of his head. In what we will come to recognize as standard Rainer deadpan delivery, she offers musings on the wide topics at hand, though her scenes also feel overly long. I would be tempted to say that this is Rainer’s least dynamic, though I may also grant that it is a film that went over my head, and one I might come to enjoy and appreciate more as I become familiar with the sources quoted.

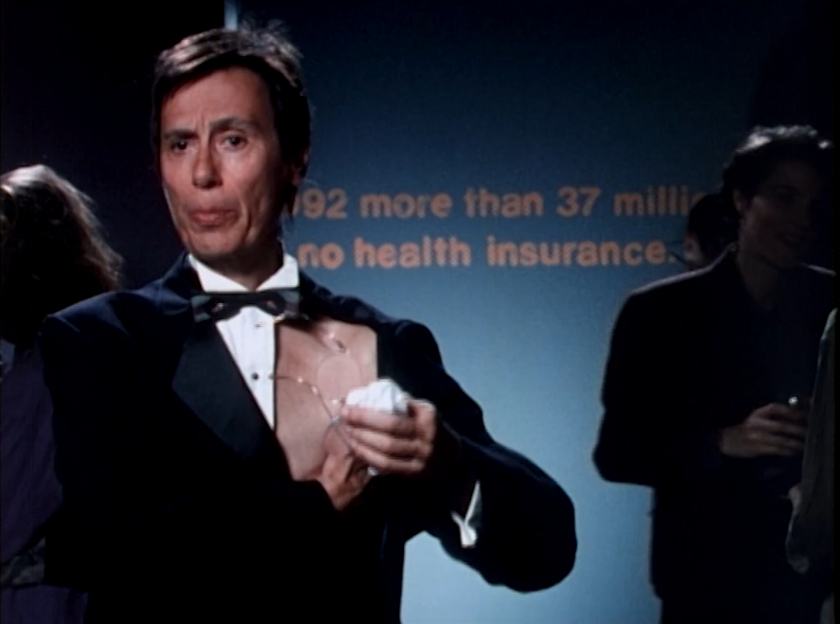

The Man Who Envied Women (1985)

The Man Who Envied Women is a rather striking dissection of the academic, left-wing or left-leaning men who use ideology to excuse arguably sexist or otherwise questionable behaviours. Starting in the most direct way possible, an interview with our lead, where he says he can admit to anything, including beating his wife, describing his faeces in great detail (I believe a more vulgar term was used), but, and note this, “please don’t ask me about the size of my bank account”. It is a comedy rather than an essay, and a conflicted, questioning approach to its themes, rather than a clear-cut thesis or message.

Textually rich, and in complete deadpan. We are also treated to a dual act for the lead, our fill-him-in character of Jack Deller (“Jack Tell Her”), who is simultaneously an open book and a question mark. Our primary Jack Deller is your perhaps most stereotypical idea of a New York intellectual, a bit of a quirky-looking gent who does not care about his hair, while the second is a tall, dark, and more traditionally handsome counterpart. The film cuts between them in the same scene or will let them replay the same motifs, with underpinnings of surrealism, and different representations of masculinity.

One of the things I found very interesting is the way it interacts with women, or rather, men’s relationships, feelings, and understandings of women, without really having significant women as characters on-screen characters – at least until the end. We hear women speak, and talk about Jack Deller, but most of our time is spent just looking at him/them as he/they pass through the world. He/they are our focal point, and we engage with this idea of “the man”, as well as what the relationship between men and women is or can be.

Rainer uses her now familiar style of quotations and essays on this very topic, sometimes reacting to them in a comically dismissive way, though here she also has a new tool up her sleeve: classic cinema.

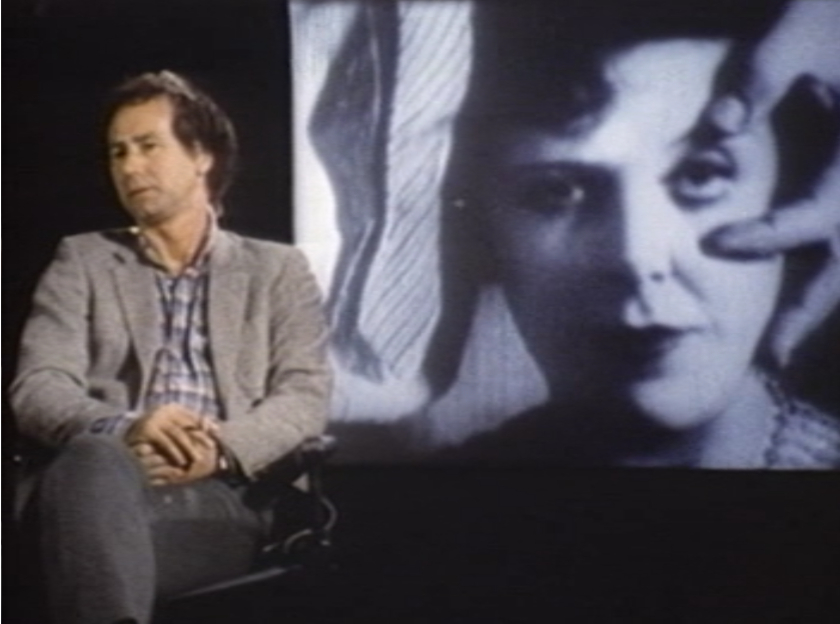

Throughout the interview sections, our Jacks sit in front of a projection of classic films, often starring Bette Davis or Humphrey Bogart, though a whole collection of films are used and cut in. Even Un Chien Andalou makes an appearance. Sometimes we merely see the images without sound as our Jacks talk, while at other points he is muted, and “they” talk. Men’s and women’s behaviour on the screen, their gender roles, gender presentations, and just an endless amount of juxtapositions take place in front of our eyes, and it is done in such a vivid, direct, funny, and dynamic way.

Like many of Rainer’s films, this may also very much become richer the more you know about the source material used, and it may indeed run the risk of being accused of being overly academic. That said, this is also something it has a little fun with as we linger on one of Jack’s dry lectures with the camera moving freely across the room, even leaving for the toilets, seemingly completely disinterested in what he has to say.

It also plays to comedy even more directly than Rainer’s previous films, a sign of things to come, with a recurring favourite of mine being endless crass statements, stories or discussions that Jack overhears while wandering around on public streets or having a meal. The camera will simply move from various sets of partners or friends as if Jack is irrelevant, a passerby, and it brightens the whole film. The film is simply not afraid of being silly, nor is it afraid of being cutting and in the end, it manages to be both.

Privilege (1990)

Smearing lipstick on her face Yvonne Rainer declares her retirement and accuses women of their inability to take power in society. She promptly recasts herself as Yvonne Washington, a black woman. This is a film about menopause.

It is also, believe it or not, once again, Rainer’s most straightforward film up until this point, even as it blossoms into all directions concerning its central theme of privilege.

Irreverent, and frequently hilarious, Privilege (the film) follows Yvonne Washington’s attempts to get women to speak about their experiences through menopause, but Jenny, an old dancer friend of hers, refuses to stick to the topic, finding all ways to deflect from it and takes her into an extended flashback/retelling of her youth, as she marvels in her own beauty and memory.

There are so many creative, fun, and Brechtian touches here, both inside and outside of Jenny’s story, which is told with so much spunk and delight. The most overt is that our middle-aged Jenny is playing herself in what she calls “flashbacks”, enjoying the whistling men and not finding the reason to remember what she looked like, or even the names of people key to her story. Equally intriguing, and balancing, we have Yvonne Washington’s staged interviews juxtaposed with real interviews conducted by Yvonne Rainer, including one that is of Jenny herself, or more likely, the actress portraying her, Alice Spivak. The blurrier low-quality “real” footage, intermixes with the brushed-up and more cinematic adaptation adding a great deal of authenticity to the discourse.

In snarky re-usage, all-male doctors from old black-and-white informational videos also tell us all about menopause, how women start to become deficient, how they can find new purpose and other frequently condescending or old-fashioned ways of seeing the process from the outside. Do you become less of a woman? Is your purpose done? Are you, as one of the many writers quoted puts it; “on the other side of privilege”?

The film opens up further, as characters within Jenny’s story start to directly address the screen, of course, reading essays and quotes, this time directly attributed by cutting to Rainer’s computer, where the author and year will be listed.

Yes, text, this time through new technology also plays a part in the intricate fabric of this film, but what’s more, it also starts digging into the privileges of women, especially white women, and re-examining itself in the context of race and class. We touch on housing, rape (including as a political tool), what women will put up with to please men and so many different topics as Jenny’s stories sprawl in different directions and Yvonne Washington stops her to ask questions and examine why she acted, thought or behaved a certain way.

A riot from start to finish, Privilege is possibly Rainer’s most entertaining film. Fuelled with comedy and just bold creative choices it thunders like a firecracker, and balances comedy, commentary, and introspection perfectly. It is simply a multi-flavoured delight, and easily Rainer’s most fast-paced. It may even be the best film to use to get into her work as a filmmaker, as it contains so much of her personality and style leading up to this point, but just with an added level of universality, accessibility, and energy.

MURDER and murder (1996)

Frolicking on a beach, a middle-aged woman and a teenage girl spot a camera crew and run toward them. The woman declares she was born in 1889, the young girl in 1943. They fight for the camera’s attention, with the teenager declaring that at least she is still “around”, and dating the other’s daughter – Doris. That one of them is still alive reveals that they are not ghosts, but perhaps still some form of apparition, and they will follow us throughout our story. They are watchers, and commentators, following the well-being of the somewhat strained romantic relationship between Doris and the now middle-aged Mildred.

At the core of MURDER and murder, and for all of Rainer’s now showy and explosive style – even stepping into the frames herself spoking a cigar with the left side of her chest exposed – or arranging a large-scale boxing match between the couple with classic Hollywood spectators as our couple battle through their problems – this is a very simple and charming love story and a delightfully human comedy. It is Rainer’s most straightforward narrative, following the couple’s problems and the developments of their relationship without really jumping in all directions. Quotations are still used, but it is rarer, and now characters will generally open a book and read a passage, rather than repeat essays as monologues.

The film is spiced up from all directions, with wacky retellings of dreams, breaks with the 4th wall, mainly by Rainer herself, and much of the bold comedic touches we have seen bubbling throughout her career, but really came to the forefront in Privilege. Political and social issues are still very much at the forefront, as the film explores reactions to their same-sex relationship, and the status of lesbians throughout history, not to mention issues of women’s health that mirror Rainer’s own life. These moments can feel very real, but Rainer’s approach to utter irreverence reframes them in bold, wacky comedy, including full-on slapstick.

Throughout this Doris’ deceased mother and young Mildred, or Millie as she goes by, watch on as the relationship struggles. Their reactions often contrast our leads, who are from different worlds and with different temperaments. Doris is an art teacher, in her first same-sex relationship, and with a daughter and son-in-law still uncomfortable when it comes to dealing with it. Mildred meanwhile is an academic and activist specifically engaged in issues of Lesbianism, which leads to clear miscommunications and uncertainties in how to engage with each other.

An early, heartbreaking scene shows Doris performing a comedy sketch she has worked hard on in front of Mildred, and our apparitions, which neither sees. The vivid applause by our visitors from the past is countered with the more stoic expression by present-time Mildred. When Doris asks what she thinks, she looks confused and starts to break down the themes of what it is about and what Doris might be expressing/commenting on in an abstract way, as we see the brightness go out of Doris’ face.

We also get many more intimate scenes and scenes of mundanity, and their relationship and tribulations are fleshed out, and this is again why it feels like Rainer’s most narrative and indeed most human work. The artistic flourishes and comedy give it life, and the real-world thematics give food for contemplation, but most of its power simply comes from seeing two people, and their love, who just feel real and raw. It does perhaps run the issue of bi-erasure, and talk about “becoming a Lesbian” may indeed seem antiquated and wrong-headed today, though its exploration of Lesbian identity, and just love, in general, strike through all of it. This is a vivid, playful, hilarious, charming, and touching masterpiece that simply has to be experienced, and truly deserves status as one of the greatest films of all time.

I do not say this lightly. Everything in Rainer’s career, from her more abstract beginnings to her increasingly loud humour, wild experimentation, and bold touches all lead to this point and culminated with something powerfully simple. The way the film moves and breathes, the meta touches, the use of text, and Rainer herself in a remarkably brave and personal turn I do not wish to spoil, deliver a kind of cinema and expression that is just not seen or experienced elsewhere.

This film needs to be rediscovered in all its glory and so does the broader work of Yvonne Rainer. Hopefully, after reading this article those of you not familiar with Rainer’s work will be inspired to at least give her a shot. My recommendation would be Film About a Woman Who… for those primarily drawn to experimental cinema, Privilege for general arthouse fans and MURDER and murder for those primarily intrigued by human drama and narrative storytelling.

I also hope that those who attempted to get into her early work but failed to find a connection will still seek out her later films, or vice versa pending on your tastes and preferences, as the differences can not be overstated. Their only true similarity is the cinematic playfulness, boldness, and unbridled creativity, strengths I’m happy to say are present in each and every single one of her films.

Christoffer Odegarden is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of iCinema Magazine. He is also the host of the bi-weekly cinephile podcast Talking Images.