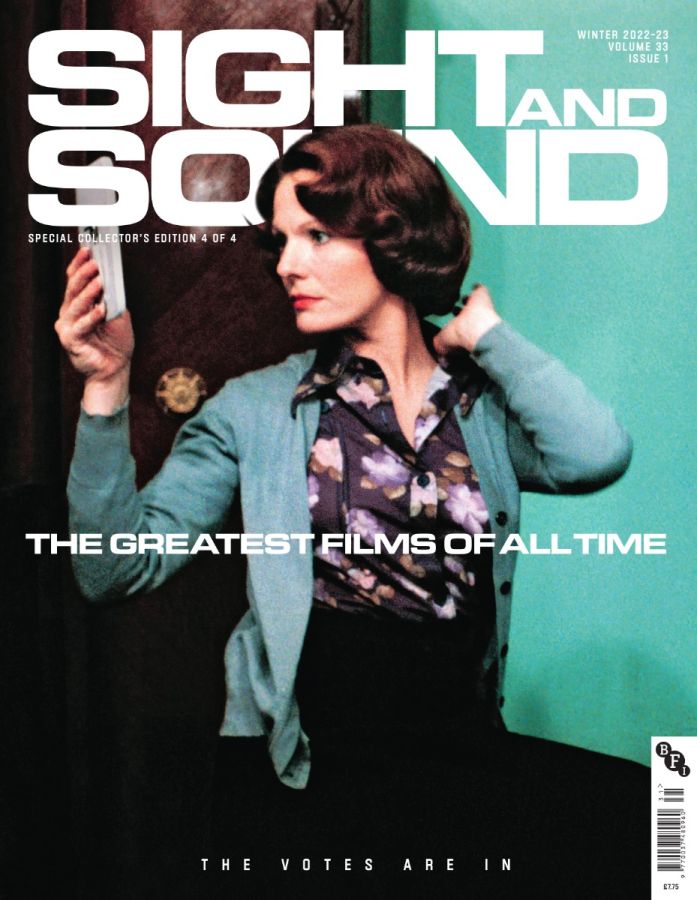

I have to admit that I was not just surprised when Jeanne Dielman was declared the greatest film of all time by the once-in-a-decade S&S critic poll, I was worried. Worried about the signals the largest poll of film critics in the world would be signalling about cinephilia. Worried that a 3-and-a-half-hour piece of slow, contemplative cinema, regardless of how seminal, important, influential, and worthy of endless analysis might just be too divisive, even off-putting. Worried “we” would be seen as even more elitist and out of touch than we currently might appear and simply, well … scare people away.

Those fears are not quite gone, and if a film teacher starts the introduction to “serious” cinema with Jeanne Dielman, many students may indeed lose interest in diving further, or write off critics and academics as mere snobs, more interested in form than what most people may call “entertainment”. We are already at a disadvantage when trying to get people interested in classic, auteur and arthouse cinema, and Dielman could indeed be the bridge too far for many.

Let’s be honest here, when luring people into cinephilia a visually lush Hollywood thriller starring Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak is a much easier sell, and that’s exactly what the previous winner, Vertigo, provided. Calling it a thriller may be underselling its power and importance, but stamped by the master of suspense, this unnerving and unusual narrative should be sure to thrill and even disturb. The use of colour and almost hypnotic visuals is out of this world and the Bernard Herrmann score could not fit better. Sure, a portion of general audiences will still be scared away by the fact that it was made more than 60 years ago and the unusual narrative may even put off others, but when balancing a gorgeous Hollywood thriller against a 3-and-a-half-hour Belgian art film the contrast is not just striking it is mind-boggling.

So why then am I becoming more content, yes, even happy, with Jeanne Dielman resting on the top spot?

A Powerful Statement on Cinema

Looking at the media zeitgeist what appears to be the most discussed element of Jeanne Dielman landing on the top spot is that it is directed by a woman, and that is understandable given that it is rare women filmmakers have this kind of top exposure, and when discussing culture, this is an easier point to grab a hold of than the actual content of the film. We must also remember that many commentators have likely never even seen the film.

Not that the gender of Chantal Akerman is irrelevant in the discussion of Jeanne Dielman. She purposefully went out of her way to place the daily repetitive routine of women on the big screen in an era when gender roles were far more clearly defined than today. The fact that the crew was primarily made up of women and Akerman’s own thoughts of showing that women could also do the roles generally held by men on a film set, will likely also be included in many detailed pieces of analysis on the film. It is part of its intent and power, and thus this may be a particularly hard case of separating art and artist.

However, when we talk about Jeanne Dielman it is generally about the powerful and radical shift in cinematic language, the recalibration of what is action and how we as viewers, at least in a successful viewing, need to view time in a different way than we normally would, becoming transfixed and spellbound by movements, time and space. Seeing daily chores because integral in character development and suspense.

Using the techniques of slow cinema to build suspense and spellbind us was not unique, we can bring up obvious names such as Antonioni and Tarkovsky, and perhaps most prominent Jacques Becker‘s exquisite prison escape film Le trou as key examples, but there was a central difference here. Chantal Akerman wanted actions generally not seen to be important, to carry the action and even build suspense. Showing Jeanne Dielman clean cabinets or prepare meals is not the same as seeing prisoners slowly hack through cement. It is not just the mode of filmmaking, though this too was more extreme than her predecessors, what the form amplified was different.

Cinemagoers would leave their homes and look up at a large screen showing domestic chores, the context of this is almost unfathomable, especially as I have sadly never been able to see the film at the cinema myself. Even in your own home, there is however something different in specifically choosing to watch actions and movements you often prefer not to think about even when doing them yourself.

The form, language and approach Akerman used in the creation of the film itself made these actions come to life, feel integral, and in the final act, where the route is ever so slightly adjusted, fill us with dread and uncertainty. She is fully successful, at least when the film works for us, to slow us down to the film’s pace, leaving us engrossed by every movement, understanding their importance and through this essentially creates a thriller of epic proportions.

Jeanne Dielman gives us a radically different view of what cinema can be from Hollywood cinema, commercial and prestige cinema around the world and even the arthouse scene at the time. It is one of the boldest exercises in the power of cinema and is integral to the development of slow and contemplative cinema.

I find it incredibly exciting, and a very powerful statement, that these attributes are highlighted and elevated in this way. This is a statement that the very best of cinema can be outside of Hollywood, outside of the crowdpleasers. It is a statement about the power of the cinematic artform, and with apologies to both Vertigo and Citizen Kane, that cinema can be … well … more.

Again, with Apologies to Vertigo and Citizen Kane (and their most ardent supporters)

There is probably no way to say this without offending a large portion of cinephiles and being branded as a snob, even if I preface this once more by preferring Citizen Kane and Vertigo to Jeanne Dielman, so I’ll just be blunt: Hollywood films are not the be all end all of cinephilia. For all their genius, creativity and artistic touches, both Citizen Kane and Vertigo are pieces of narrative cinema. They are driven by story and/or characters not cinematic form, even if Vertigo can be argued to blur that line.

Can I manage to bring myself to be so condescending as to describe these two masterpieces as “starter” films? Perhaps I can. Not that this is an insult by any means, it is a strength and why many likely hold them so dear. They simply have the breadth and accessibility to reach across most aisles of movie fandom. These two films are masterpieces that can indeed lure the non-initiated into our ranks, which is why neither crowning the poll can be a little scary.

The top entries are no longer a “basic” starter pack to make people “comfortable”. We are now firing on all cylinders. It is a bit like the sneaky drug pusher of cinephilia skipping all the gateway drugs and offering the school kids pure heroin.

But is that necessarily a bad thing? Do we need to sneakily hide who we really are?

The further you get into cinephilia, the more you watch, the more you tend to crave something different, the more you tend to look at form and the more you tend to embrace cinema as an artform. In the past, the films that go beyond narrative cinema or stretch the idea of narrative cinema, even cinema itself, have gotten seats at the table, but the caveat has always tended to be a big, accessible film. This makes complete sense, as they have the power to get consensus more niche or challenging films do not, but now, it has changed.

The implication is that Hollywood cinema and traditional narrative cinema are the height of cinema and that diving into Akerman, Rivette, Tsai or even Godard, Bresson and Tarkovsky is more of an added besides. Niches you should certainly check out, but not as great examples of the power of cinema as Citizen Kane and Vertigo. Arthouse cinema, and especially experimental cinema, being held a bit at bay, and never getting the opportunity to fully shine.

Placing Jeanne Dielman on top is a bit like ripping off a band-aid and saying “welcome to cinephilia”, this is what we like!

The List is Not Really for the “Paying Public”

One of the complaints you may see, especially on social media is that the list shows how far removed critics (and academics and programmers) are for your average film viewer, but that was already the case. In a piece for The Guardian/The Observer titled, “Lights, camera, controversy“, critic Philip French commented on the controversy over the list a full 20 years ago, the lack of recent films and how out of touch the list was with the paying public.

Even Vertigo, the stylish Hollywood thriller, is not what your average filmgoer will sit down and watch unprompted, nor is Citizen Kane. The list already was and has always been for people who have a specific passion and love for cinema. The listmakers are not highlighting the latest and greatest blockbusters, but the films that for various reasons stood out to them as being amongst the greatest films of all time. What each participant puts into this varies, from those believing in objective criteria or investigating influences and impact, to those going by pure love for the individual films and nothing else, but what all (hopefully) have in common is their love and passion for film.

Critic Roger Ebert once described the list as “By far the most respected of the countless polls of great movies – the only one most serious movie people take seriously.”. Some discussion may be placed upon who these “serious movie people” are, and who of us may be deemed worthy, but the notion is clear: this list is not for regular moviegoers or even casual film fans, it is a look at the depths of passion and knowledge of cinema.

So … of course, it is “out of touch”, it bloody well should be. The only reason it would ever be acceptable for it not to be out of touch is if the average filmgoer becomes as obsessed as “us”, but that is unlikely to ever happen.

Don’t Worry, New Film Fans Are Unlikely to Go for S&S First

One of my biggest worries with Jeanne Dielman scaring off new film buffs is broadly unwarranted. The Sight and Sound lists (people are talking so much about the critics’ list that you can almost forget the directors’ list) are unlikely to be the first stop for someone slowly trying to expand their cinematic palette and try films outside of their comfort zone.

When I was first expanding my interest in cinema, it was through IMDb’s top 250, which I then, years later, started following up with the They Shoot Pictures Don’t They list and S&S. Today, Letterboxd has clearly usurped IMDb in terms of younger audiences, and their official Top 250 Narrative Feature Films, is likey a far more common place to start.

Film viewers getting their start here will not go through Jeanne Dielman but The Shawshank Redemption and The Godfather in the case of IMDb and Come and See and Parasite on Letterboxd. The winner of the Sight & Sound poll is nowhere on IMDb, where it neither has the rating nor vote to qualify and is only 176th on the Letterboxd list, at the moment coming in 6 spots after Terminator 2 and two spots ahead of Star Wars.

It could be argued that a film like Jeanne Dielman will always struggle more when a list is based on average ratings rather than overall supporters due to its experimental and divisive nature, but even in our community poll it struggled, coming in at 418th on the ICMForum’s Favourite Movies 2022 Edition. Could this be because a part of our community has not yet seen the film? Or is it that critics, academics and indeed filmmakers (it placed 4th in their poll) value it more than regular cinephiles, making it an even more “specialised” favourite?

Regardless of how Jeanne Dielman itself fares, regular film viewers being groomed by the big cinephile machine, will likely not be exposed to it until they are ready for something outside of the narrative canon. It’s ascension does not mean that people won’t continue to see Citizen Kane and Vertigo first. The only thing that has changed is that the most dedicated and passionate of us must now take positions on and (unless we stop ourselves) passionately discuss and dissect Jeanne Dielman over the coming decade, and that’s not too bad of a proposition.

But … I Still Have Doubts

In the run-up to the publication of the Sight and Sound lists, I was attempting to write a piece titled “In Defense of the Canon“, which I could never bring myself to publish or finish. In it, I would have made almost the opposite argument that I make in this article. I pressed that the value of the Sight and Sound lists to be its impact on broader society and average film viewers to take the plunge and finally see Citizen Kane, Vertigo and Tokyo Story and that we should not be quick to push

While S&S has always been niche, the more accessible nature of the “niche” films, especially in light of the media buzz, makes it an important event for the entire cinephile community. This is a time when people actually stop and listen to us, and maybe I am wrong when I say that younger and less experienced film-viewers won’t take notice. I’m sure many are actually sitting down to see Jeanne Dielman for the first time, and far fewer are likely to be ready for it than they may be for previous winners. Will this be a case of Jeanne Dielman being people’s very first foray into experimental cinema, contemplative cinema or arthouse cinema overall? Quite possibly.

Luckily, there are so many lists, so many respected films and so many places to get recommendations that seeing and disliking Jeanne Dielman is unlikely to actually scare people away. It is easy to see that this film is a, shall we say, a peculiar case unlike most else out there, and when all that is said, should we really undervalue people to the point that we will assume they won’t get anything out of such a viewing, even if they are not prepared?

Time will tell how much this outcome will affect our community, but as someone who has always wanted arthouse to take a larger part of the cinephile conversation, this is a very exciting time to discuss film. Would Jeanne Dielman have been my choice? Far from it! But I am starting to appreciate what having a film like Jeanne Dielman at the top of a list does to us as a community and the conversations it is already starting to create about what cinema is and should be, and that is a very good thing.

Christoffer Odegarden is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of iCinema Magazine. He is also the host of the bi-weekly cinephile podcast Talking Images.

Well done, Chris. You have articulated all of the good reasons for Jeanne Dielman’s ascent

You have done a very good job at pointing out the positives of this result, which I also agree with, however there are other things at play that not only disturb me but undermine the “stature” of the poll.

Ignoring the influence of “cancel culture” which to me is as dictatorial and suppressive of what it seeks to replace, and other reasons why certain films vaulted into the top 100 makes your argument very one-sided, especially since you have flippantly brushed them aside, when it is obvious to me that they are a part of what took place.

I’m inclined toward seeing the “shakeup” as a good thing overall, for reasons I have stated in the message board thread, if only because of the antiquated vise-grip that existed before, which may have been more canonical, but only if the last 40 years of cinematic achievements didn’t exist.

What concerns me, now, is the way “politics” and “critical trendiness” may govern the poll in the future, though perhaps this was always the case in some sense.

Thanks, Cinewest. In the case of this article, I wanted to focus on the advantages of Jeanne Dielman claiming the top spot, rather than get into the controversies around the latest poll, which tends to move away from cinema and into the cultural sphere (or in some cases even conspiracy theories). The reference to publications highlighting the gender of Akerman was not intended to reference the controversies, but much of the positive press surrounding the release of the poll and what many mainstream publications felt was the most relevant to report on.

I do share your concern that it is quite possible voters thought twice about what they included in their ballots in order to not receive some kind of backlash. I hope that’s not the case, but the internet can be a very volatile and hostile place. Similarly, I also think “critical trendiness” and “politics” likely played a part, though like you, I assume this was always the case.

And then you also have all the unspoken “rules” many are inclined to follow. If you did not read it this is an interesting commentary from Sight & Sound highlighting what the author believes is a common practice of essentially, to paraphrase, “showing off”: https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/features/poll-position-taxing-task

Excerpt: “If professions need gatekeepers to maintain a set of standards and decorum, then in the case of film critics and scholars the function has become twisted and all too predictable in its mix of sobriety and pretension, genteel shock value and barely controlled narcissism.

There are basic ground rules, to be sure, as easily discernible as a recipe book’s ingredients: something mainstream to show populism, something avant-garde to show hipness, something old, something new, something borrowed (from another culture, perhaps), something blue, or more likely noir. Be sure to include a title that nobody knows as well as a title that everyone knows, include one long scorned or long treasured.

[…] We are not ranking films, nor cinema history – we are ranking ourselves.”

I think that the comment you quoted is spot on, and what rises to the top in situations like that are the films that have less competition for a spot on a list of 10, which will thereby amass more support. I believe this was part of the success of silent films in 2012.

Still curious about what might result if the submission list were greater in number, ranked, or perhaps broken into categories