It started with Monica Vitti and ended with TV movies and a venture into sexploitation so “extreme” that it was seized twice by the Italian police. Miklós Jancsó‘s tenure in Italy has hardly won him any acolytes. The films never have and likely never will feature in lists of his greatest work. The only historical footnote remaining is about exposed genitalia and fellatio rather than their artistic value. This is a shame, as the films are in no way a departure from Jancsó’s filmography, neither in craft nor in ambition.

The move to Italy came at a time when his star could hardly have shone brighter. He had established himself as one of Europe’s hottest and most respected arthouse directors with an incredible run of films, including The Round-Up (1966) and The Red and the White (1967), both frequently considered among the best films of all time. Producing films in a far more exportable country, and with far more exportable stars, could easily have broadened his appeal, and cemented his name further. However, instead of attracting larger budgets and continuing to work with Italian and French stars, his star faded.

It is important to understand that this was by no means a blip or a quickly abandoned failed experiment. Jancsó lived in Italy for a decade and produced four Italian feature films between 1970 and 1976. He also shot an even more difficult-to-find documentary about Pier Paolo Pasolini’s staging of the play Calderón, which was released in 1977, and a Hungarian-Italian co-production in 1981.

This is the same as the entire output of many other European masters in that decade, and what’s more, it was not all he did. He consistently travelled back and forth between Italy and Hungary, where he continued to make films, including his legendary Red Psalm (1972).

So, what if anything went wrong and are these Italian Miklós Jancsó films worth seeking out?

How Miklós Jancsó Ended Up in Italy

It belongs to the story and may illuminate the relative failures a little more to explain that Jancsó did not move to Italy first and foremost to advance his career. He moved for love. He had fallen for actress, writer and later director Giovanna Gagliardo, whom he not only lived with but worked with for a decade.

All his Italian films, as well as the 1981 Hungarian-Italian co-production The Tyrant’s Heart, were co-written by Gagliardo. She did however not work on his Hungarian efforts in the 70s, adding a special layer to these four Italian films in that they are works from both of them, rather than his alone. The end of their relationship marked the end of his work in Italy, which gives us the question, how intriguing is this work? What can Miklós Jancsó fans expect to see here?

Did They Spend The Entire Budget on Star Power?

The reason why Miklós Jancsó did not have a good run in Italy and failed to attract star-power again can perhaps be explained by his very first Italian venture: The Pacifist (1970). Coming in hot he did not only pair up with Italian superstar and Antonioni icon Monica Vitti – he extended his reach by including French star Pierre Clémenti, eager to work with yet another arthouse master. I’m not even sure if its failure to launch and capture a similar degree of acclaim to Antonioni and Buñuel is entirely Jancsó’s fault – if his at all.

While I would personally rank The Pacifist as the weakest Jancsó film, the direction is nearly flawless. He creates the same eerie, fleeting, circular dance we know and love. Italy’s streets come alive, as does near-nightmarish fear as Monica Vitti is stalked by murderous Fascist hooligans, sneaking around every corner, surrealistically gallivanting around with murder in mind. To give a hint of the issue: if you muted the film it would look just as impressive as any Jancsó from the period.

So what is the issue then?

It is: “talky” and clearly not in the way that it was originally intended. Watching the film you would think the producers interfered in the post-production and added arbitrary voice-over, as, most of the time there is dialogue the characters are not actually speaking …

There is some interesting things that come from this, for instance, entire conversations between Monica Vitti’s character and her never-seen mother, being played over entirely unrelated visuals. Did Jancsó do this on purpose or did someone else do it for him? It is certainly a creative way to elaborate on characters and add extra tension – but the thing is, with Jancsó, the characters are never really fully-fledged characters, and when he takes us on these dances of violence, we are usually left with much silence and wander into the world. The near-incessant talking, be it inner thoughts, past conversations or conversations happening in front of us without their lips moving, just felt really off.

Even when the characters were actually speaking, the audio felt a little off. Comparing it to his TV films, the production values on the dubbing – which is how all Italian films were done at the time, with the sound added in later – felt subpar, to say the least. It takes you out of the suspense and the atmosphere and makes it much harder for the film to be effective.

This is a shame, as, while it is unlikely that The Pacifist would have been considered amongst his best works regardless, it would have been on par with his 70s average. His popular collaborators Daniel Olbrychski and József Madaras are always present as the ringleaders of the Fascist thugs and are every bit as ambivalent, intense and unnerving as they tend to be. Pierre Clémenti really dove into the style, uglifying himself with a kind of erratic junky energy (granted, that may not be that far from his real life at the time), and Monica Vitti is strong as usual.

All the pieces more or less fit beyond the sound, and with the star power and more exportable Italian production could have done a lot for his career if it was actually been polished. A great shame!

Diving Into Italian History for TV

If you followed Jancsó’s Hungarian career you know that so many of his films took inspiration directly from Hungary’s history, and converted them into metaphorical, enigmatic and surreal dances of violence. One of the most exciting things about his ultra-obscure Italian TV films, beyond the fact that they are surprisingly great, in part because of their limitations, is that they immersed themselves in Italy’s own past, creating two play-like journeys into the Roman era and powerful, real-world figures.

These TV movies did not sport Italian stars as the leads, but rather used József Madaras and Daniel Olbrychski, giving each their own vehicle. József Madaras became Attila the Hun himself, showing his preparations to invade and conquer Rome in The Technique and the Rite (1972), which of course ties fully into Hungarian history as well. Meanwhile, in Rome Wants Another Caesar (1974) Daniel Olbrychski became Claudio, a rebel leader in the time approaching and after Caesar’s assassination.

Rather than the beautiful wide-screen shots we know Jancsó for, these films were shot in a squarish TV-friendly 4:3, and the films are also far less visually vibrant. This more drowsy starting point is however used as a strength, setting the films in equally drowsy settings, with stone or desert sand enveloping the frames. The sparseness of the splendour gives them a lo-fi minimalist vibe his previous films did not have.

The films still have what I have come to associate with Jancsó above all else, a kind of enigmatic lyrical, circular and choreographed expression that feels like a dance, but in contrast to many of his films, they also feel like classic plays. Both stories were written by Gagliardo and Jancsó, and have no other mentioned sources, but this is very much the sense you get – complete with long and large monologues. In many ways, they are both quite comparable to his Hungarian Elektra, My Love (1974), which indeed was based on a play.

This may make them more suitable for a slightly more niche audience, but if you can picture a merger of Jancsó, Straub/Huillet and TV you will be in the ballpark – and they really do live up to Jancsó’s more visually appealing work.

The Technique and the Rite (1972) is every bit as enigmatic and unease-inspiring as in their other collaborations, only here he is the godlike Attila. He is the centre at all times and appears to possess magical powers. The film is mystical, and as usual, likely heavily metaphorical in ways I would love to read in-depth essays by experts on Hungarian and Italian history. We see how his followers react, the lies, the brutality, and so much more, all set almost exclusively on a single beach, with harsh violence brushed away by the minimalist touches. It is a great and unusual experience, adding a slightly different edge to his work that at least should intrigue hardcore Miklós Jancsó fans.

Rome Wants Another Caesar (1974) is the most impressive of these two works, in part for infusing an existential anarchist/democratic philosophical debate into the context of Caesar’s succession. Daniel Olbrychski casts an intriguing shadow as the freedom fighter who gets the option to join the new Ceasar and help him rule, when he doesn’t think a Caesar should exist at all. Similar magical elements to The Technique and the Rite adds extra flourishes, but it is the philosophical dialogue, the familiar dance of violence and the lo-fi minimalist touches that make this film pop and feel more special than its near non-existent reputation.

Too Lewd, Even For the Italians?!

We know Italians, especially the Italians of the 70s loved their nudity and just general naughtiness. This was the country where full-frontal female nudity was commonplace, sex comedies and pulpy sex and nudity-fueled crime and horror films were pushed out in insane numbers and, in 1976, had Pasolini releasing the infamous Salo. So, why is it, that in the very same year, the police went after Jancsó and Gagliardo for crossing the line?

The answer is in the sex acts that Private Vices, Public Pleasures bring to the screen, including unsimulated male masturbation in full view. The police also had an issue with implied fellatio, and, unusually, it was seized twice, rather than once. They just would not let it go.

On an interesting flip side, this was a film that gave Jancsó and Gagliardo relative financial success, and looking at IMDb and Letterboxd it is actually his most seen film of the 70s after Red Psalm and Elektra, My Love.

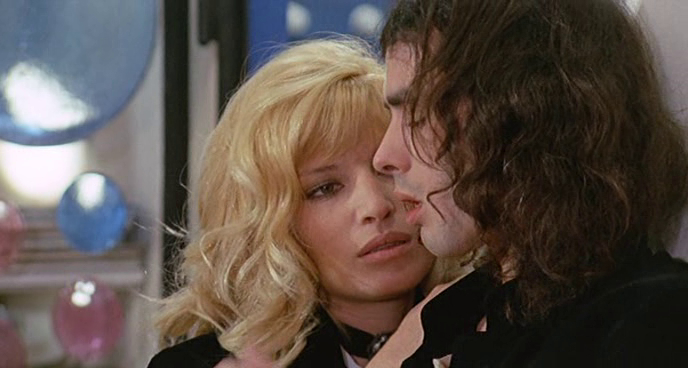

I have to admit that I went into this film with some trepidation as I just didn’t know what to expect beyond the fact that it is explicit, and frankly, I quickly realized that I might be pleasantly surprised. Private Vices, Public Pleasures plays much more like a comedy than any of Jancsó’s previous films and just delights in being naughty. Its characters display utter chaotic energy and they run, jump and roll in stunning surroundings – that is once again depicted with beautiful widescreen visuals.

In terms of the quality of the craft, the film is breathtaking, which may seem absurd given the content, but it is just beautifully crafted and filled with so much energy. You never really see Miklós Jancsó having this much fun. Dread is almost always in the mix, while here we get sneaky and cheeky games and just a lot of freewheeling insanity as he brings us into the world of royal excess.

While certainly banking on getting the audiences into the seats with sex, Private Vices, Public Pleasures also displays many of his traditional themes of power structures, and Austro-Hungarian history (the story is based on the Mayerling Incident). Our protagonist is the crown prince, rebelling and attempting to delegitimize his father with his scandalous lifestyle, waiting for a reaction that may be more extreme than what he expects.

The dance is very much still alive, as are the long takes, and everything we love about Miklós Jancsó. The main difference is that until we near the end it is a dance of cheeky entitled fun and frolicking, rather than violence or dread. I could not resist smiling and while it in many ways is far from Pasolini, you could recognize some of the same naughtiness as in his erotically charged Trilogy of Life.

A Soft Goodbye to Italy

It is interesting to note that his very last collaboration with Gagliardo, his very last film with Italian ties, The Tyrant’s Heart (1981), also called Boccaccio in Italy, feels like a gentle goodbye to Italy. We once again see Italy and Hungary merged, with a Prince raised in Italy and joined by his faithful Italian aid and a troupe of actors as he returns home to find his father dead and his uncle romantically entwined with his mother.

If that sounds like Hamlet, that’s because it, well, feels a lot like Hamlet, but with a special Jancsó twist, with everything from a near-vampiric mother seemingly killing a young woman every night, orgy-like scenes of naked bodies (though quite toned down from Private Vices, Public Pleasures) and the degree of mad whimsy not only continued but lead by Pasolini regular Ninetto Davoli – the faithful Italian companion.

József Madaras is back as the all-imposing uncle, and he is as captivating, if not more so than ever, with wild antics and chaotic energy you can never determine. What is his goal, what is his aim, and is he the enemy? It is incredible to me that he could keep taking on these roles for Jancsó and keep performing them to perfection, each with their own tweaks, but always with the same uncertain unease. Daniel Olbrychski is also back, this time as a Turkish “friend” of the father with increasing screentime.

The film feels like the staging of an ambitious play, with constantly moving parts, and loves playing around with its spinning, uncertain world, where you never know what is real and what is make-belief. It is set almost entirely within the castle and it feels like an elaborate stage in the best possible way – in part because it literally is. While centring on the Hungarians, and the prince, his mother and uncle, in particular, Ninetto Davoli and the acting troupe are ever-present, hiding and disguising moments that could seem serious. The threat of death is always being laughed away, but also ever-present, with the Italians being the ones to amp up the film’s more ludicrous elements and complete the spectacle.

The Tyrant’s Heart is a playful goodbye to his Italian period and a nice showcase of just how similar his Hungarian and Italian films actually are. Perhaps, in time, the consensus will come around to the same thing.

Christoffer Odegarden is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of iCinema Magazine. He is also the host of the bi-weekly cinephile podcast Talking Images.