Lazy is a critique you rarely hear thrown at Wes Anderson, and yet, for all its meticulousness, The French Dispatch fits the bill. Odder yet, the issue rests at its very core, namely the idea to present the film about a New Yorker-inspired magazine as if the film was a magazine itself. While thoroughly inspired in and of itself, the approach appears to have simply been abandoned mid-way or perhaps only thrown in as an afterthought.

Whether he was simply unable to kill his darling or through direct sloppiness, Wes Anderson could not commit to the form. There is clear evidence of this from the very beginning, but with the third and final feature, starring Jeffrey Wright as the James Baldwin-inspired Roebuck Wright, any inherent logic to the piece as a whole is thrown out of the window. Worse yet, the oversights could have been very easily fixed.

Why did one of cinema’s best-known perfectionists get so sloppy with a film that is otherwise so meticulous?

What’s the Issue? (Pun intended!)

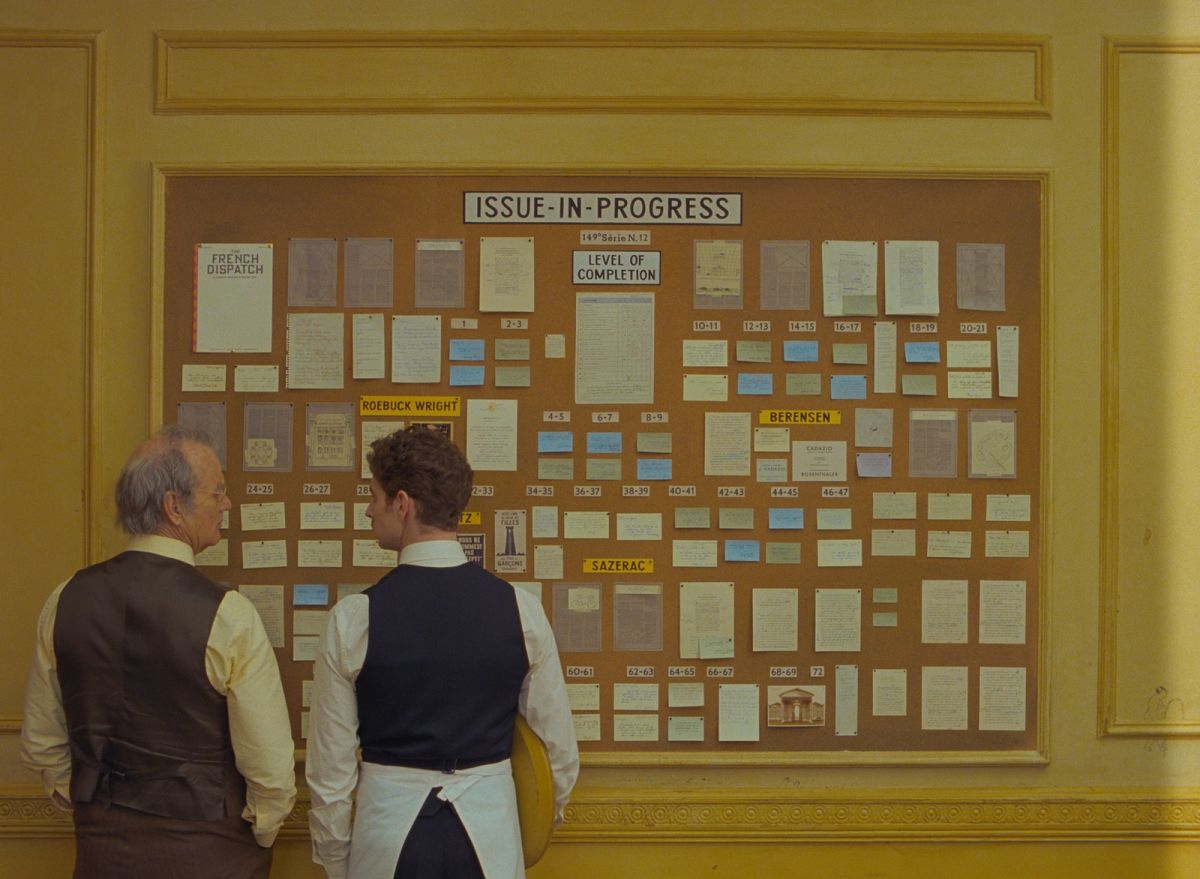

The film’s very first story, the obituary of Arthur Howitzer, Jr. (Bill Murray) plays out exactly as if it was a newspaper article, though of course, with all the quirks and visual flavour of Wes Anderson. This is where we are informed this is the last issue of The French Dispatch, as it is stated in Howitzer’s will that the publication should cease upon his death. Here we are also informed by our narrator that this final issue is to contain “an obituary, a brief travel guide, and three feature stories”. We are even given the complete index, showing each of the stories and even the page numbers.

The idea may just be a gimmick, but as an experiment, this is something I am not sure we have ever seen in cinema before, and certainly not in a production of this size. I’ll apologize in advance if I am being pedantic in my critique; perhaps it is my general interest in cinematic form that is driving my slight disappointment. Even so, I was relatively quick to forgive the little epilogues to each story, where we see the feedback Murray’s character gave to each of the featured stories and how he interacted with his writers. This could after all simply have been a flourish, a sign of love from the writers, giving Howitzer a place in their stories in his honour and memory. It could also be seen as Anderson not so much creating the film as a filmed magazine, but conjuring up an experience of everything around the magazine and its creation.

Besides this, the travel guide and the first two features actually live up to the premise quite well, especially the Travel Guide starring Owen Wilson and the feature “Revisions to a Manifesto”, lead by Frances McDormand. The first feature, The Concrete Masterpiece, does feature the framing device of Tilda Swinton’s J.K.L. Berensen delivering her story as a speaker to a large audience. A “mistakenly” placed nude in her slideshow would likely not have made it into the article, but this easily works as a flourish to amplify her personality and visualize the more descriptive parts of her story.

A similar framing device is then used in the third and final feature and this is where the structure and form are, well, as mentioned in the intro, thrown out of the window.

The Roebuck Wright Interview is Purposely Set After the Story is Published

There is something different and odd about the framing of the final feature, as, in contrast to J.K.L. Berensen simply narrating her story and giving facts, we witness a TV interview, likely set sometime in the 70s that features a two-way conversation between Roebuck Wright and talk-show host Liev Schreiber. This is, however, not the breaking point (even if the article would clearly not have dialogue from an unrelated talk-show host), rather, the issue is the entire framing as the interviewers push Roebuck Wright on his typographic memory to wow viewers.

One of his old articles is chosen as a sample case, and the article in question is the one we will be watching, the final feature of our film “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner”. Note the emphasis here. This is not a fresh article. It has already been published. How long ago the article was published is unclear, though the implication is that it is certainly not his latest and given the aesthetics of the 60s in each of the features and the aesthetics of the 70s in the interview it has most likely been a few years.

The film is suddenly no longer about the last issue of the magazine, or even the process of how these articles came to be, we are randomly in the future looking back at it all. If we were to believe we are seeing a filmed version of a magazine, this is not entirely out of the window. It is done, published and possibly published a decade ago. The fact that we are in the future is barely touched upon beyond the introduction of the story, though the narrative of the feature is occasionally interrupted for more questions and answers with the host, and this part of the segment is fairly pronounced.

This imbalance between the features we have been seeing from the 60s, and this odd add-on is enormous, and while it hardly ruins the film (after all, we are talking about less than 5 minutes of content that is perfectly strong on its own) it does break the basic idea of what The French Dispatch seemingly set-out to be.

Did Anderson’s Love of Baldwin Interviews Make Him Inconsistent?

While this is solely speculative, it may be Anderson’s desire to truly capture each of the legendary writer-caricatures that lead him to include this oddly out of place and “futuristic” framing. If you have not seen James Baldwin in studio, it is highly recommended. He was on full show in the great and relatively recent hit documentary “I Am Not Your Negro“, and you can of course find several interviews online.

Jeffrey Wright as the James Baldwin-inspired Roebuck Wright is certainly one of the highlights of the film, and the temptation might simply have been too big. Let’s be frank, the charisma present in the scenes with the unnamed talk show host portrayed Liev Schreiber is absolutely delightful. They allow exposition, show Roebuck Wright’s charm and work quite well in terms of character introduction, though it is still difficult to ignore the one sole issue that we’re suddenly well into the future.

There Was Even An Obvious Fix

If Wes Anderson wanted his form to work, he could have seen to it without cutting a second by adding a single line, or perhaps two, to the narrator’s presentation of the film’s structure. All he would need to communicate is that the writing staff had selected three stories from the magazine’s run, re-edited them and in honour of the late Arthur Howitzer, Jr added short anecdotes of how he received each story.

This way, every creative choice that currently breaks from the form would fit perfectly, and of course, such footnotes are entirely within Anderson’s voice and style.

This is also not the only solution, and Wes Anderson, had he followed his usual perfectionism, could have done any number of small alterations, including killing this particular timeline breaking darling. But alas, for some reason he chose not to.

Perhaps he did not even notice? Perhaps he just did not care? It is even possible it was always intended to be presented as a republication of these features, but the clarification was never included. You could even theorize that it is somehow an inside joke or a purposeful imperfection. However, these are questions only Wes Anderson and the team working on The French Dispatch can answer.

Does it hurt the film? Not particularly. The scenes themselves work remarkably well and allow Wright (both character and actor) to shine. However, seeing Wes Anderson being so sloppy in his approach, that he overlooked an obvious time jump, feels so out of character that it remains perplexing.

Christoffer Odegarden is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of iCinema Magazine. He is also the host of the bi-weekly cinephile podcast Talking Images.