When I think of Jean-Luc Godard the first image that comes to my mind is from the very intro of Numéro deux (1975). True to the title there are not one, but two Godards. He stands in profile at the left of the frame, arm resting over a TV, on the right we see a large camera, reels rolling. His face is in the dark, and everything above his nose is cropped out of the image, and yet, we can still see his face: it is on the TV, being recorded and projected simultaneously as he starts to make his opening remarks.

What he says is not so important in the context of this almost dreamlike visual in my head, it is rather the visual tension. The camera takes the main space in the frame, while our eyes are drawn to the lights of the TV. The soundscape is that of the recording itself. Every piece of the image and “text” is informing us that we are watching something that is created and projected. Moreso, he manages to create pure cinematic tension with very simple tools. This idea of cinematic tension, what can drive it and what can hold the attention of an audience remained vivid from his first to his last film.

The scene, or rather my recollection of it, flares up even more vividly today as it was announced this morning that Godard, the person I consider the greatest director to have ever lived, has passed. Even at the age of 91, it still came as a surprise. Last year he revealed to the International Film Festival of Kerala that he had written two more scripts and planned to direct them before he retired. Unless secretly made, the hope for more challenges to our conceptions of cinema must now be left to other directors.

Godard experimented with space, colours, sounds, framing, light and even fonts, slowly building a vocabulary we knew, while always testing out new ideas. The colours of the French flag, red, white and blue, are likely cemented into the mind of every Godard fan, as is music that suddenly stops where you don’t expect it to. Dissection entered his world to a greater and greater extent, as did analysis, but as I think of Godard the second image that comes to my mind is that of Godard the fool. Be it caricatures of himself, such as the obsessive incarnation giving his niece undue attention in Prénom Carmen (1983) or the Tati-like figure of whimsical bliss in Keep Your Right Up (1987) or his bizarre get-up, with wires coming out of his hair in King Lear (1987).

This was a filmmaker that never took himself seriously and used humour and sarcasm to even bring down himself. There is not one film by Jean-Luc Godard that is devoid of humour, even if occasionally bleak, and he could contrast deep analysis with instant idiocy. He loved word games, silliness, misunderstandings, and associative games, and was not afraid of just getting a little bit juvenile and crass. A third image that comes to my mind, is from his Dziga Vertov Period, more specifically Vladimir et Rosa (1971) where he and co-director Jean-Pierre Gorin, both dressed as part of the legal system, Gorin as a judge, Godard as a cop, unzip their pants and pull out portable video cameras. Even at his most political, Godard found time for comedy. All his cinema is coated in it, and it must never be forgotten.

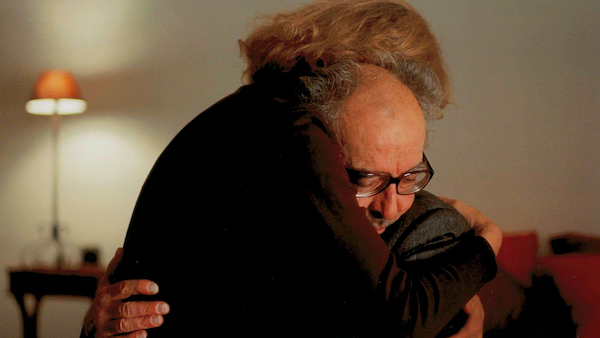

Another image I have of Godard is not by him, but by his long-time partner, both in romance and in filmmaking, Anne-Marie Miéville. She made two films starring Godard in the male lead, We’re Still Here (1997) and After the Reconciliation (2000). The former stars Aurore Clément as a clear Miéville stand-in and the latter stars herself. My thoughts are certainly with her, and whatever truth she may have captured of their relationship in these two wonderful films.

These memories I have of Godard are stronger because they were caught on film, a place he was not afraid to put himself. If I think beyond Godard and to his films, my mind will of course have to go back to the 60s and his early films. I think of the music and colours in Contempt (1963), Belmondo with his face painted blue, Karina, scissors in hand in Pierrot le fou (1965). There are so many iconic images, ideas, feelings, gestures, dances, etc. that have etched their place in my mind and cinema history, and of course, this is the decade Godard is most remembered for. Mentioning the list of masterpieces made in this period would be too extensive, though Vivre sa vie (1962) and Alphaville (1964) certainly require inclusion.

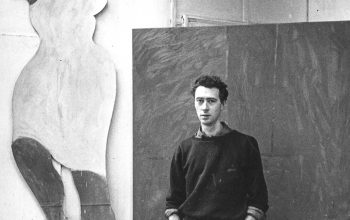

This was the decade when his films had commercial appeal and he seemed the essence of cool with his characteristic dark glasses and equally aesthetically bold lead characters. His perhaps most treacherously regurgitated quote is “All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun”, shows you his attitude and eagerness at the time, while it also paints a very wrong picture of a man who would not wait long to prove that you do not even need these basic tools to make a memorable experience.

In fact, he didn’t even need a camera. In A Letter to Jane (1972), the only visual we see is a photograph of his then-recent collaborator, Jane Fonda, or to bring up the scene I mentioned in the beginning, he just needed a camera, a TV screen and himself to set the mood and captivate us.

We should never forget that Godard tackled the basic idea of a girl and a gun already in his feature film debut, Breathless (1960), where Belmondo had the gun and Jean Seberg was the girl. The film was a freewheeling’ riff on noir aesthetics that helped popularise jumpcuts and let cinema feel free, alive and passionate. He proved to be the quintessential young auteur set to shake everything up, and even Hollywood took their cue. Bonnie and Clyde, and the entire New Hollywood movement were built on the shoulders of Jean-Luc Godard, though he was hardly impressed, especially by how slow the Americans were in trying to catch up.

He continued to play with the conventions of Hollywood cinema and establish his own unique style as the 60s progressed, and the need for something as banal as a girl and a gun as building blocks had long since passed, even if one of his most legendary shots is of an armed Anne Wiazemsky, kneeling down behind a wall built of Mao’s Little Red Book, an almost literal wall that would soon sever Godard from the popular consciousness. A wall that very clearly went up at one exact point: 1968.

Godard made 15 solo features between 1960 and 1967, and they have all been canonized to one extent or another, but beyond Sympathy For the Devil (1968), there is a decade-long gap of general radio silence in critical acclaim. The reason for the change is clear and in large part self-imposed. As time passed, simple stylistic exercises were not enough, he was more and more captivated by form and moved by the failed revolution of 1968 he also took a strong political stance.

Godard joined a Maoist collective known as the Dziga Vertov Group, first directing under his own name, then removing it in favour of the group as a whole, attacking the idea of auteurship the new wave directors brought to the forefront. His films became more experimental and more political and with A Film Like Any Other (1968) he even decided to troll his US audiences, releasing the film with the French audio and English dub playing simultaneously.

It may simply be the effect of removing his own name, or the essayistic nature of the films that put audiences off, but they should have been prepared. If you take the three films he made in 1967, namely 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her, La Chinoise and Week End and merge them together, you get a pretty good visual of what his films in this period would be.

The films they made were fueled by theory, but even if you do not share their ideas it is hard to ignore the cinematic ideas at work and the fact that the theories also involve the images in front of us. One of the most striking films the group ever made, Wind From the East (1970) has the central premise that narrative/character-focused cinema is a product/instrument of upholding the status quo. To express violence and death, they simply threw buckets of red paint. It is beautiful, hypnotic and engages in active debate and partial self-deconstruction.

Drifting away from the group, and reassessing his views, Godard would meet Miéville, who was at the time working as a photographer, and soon they started their production company, Sonimage. The partnership would see them delve into video art, play on projection, screens and analysis. They would even produce two experimental TV series, and allow themselves to play with this slightly different medium in new and exciting ways. The partnership also saw a change in political expression, looking for instance at gender roles and the nature of the media, and even the humour started to be toned down, especially the snark and crassness. The video art aesthetics and the play on glitches, flaws and limitations would also play a role in the films Godard would make all the way to his final film.

The 80s saw the birth of a new Godard, or to some a reborn Godard. While not quite returning to his “former glory” in popular consciousness, he once more started to enter the popular conversation. Every Man For Himself (1980) marks his comeback, and with a film like Prénom Carmen (1983), many saw him returning to his roots with “a girl and a gun”, while Hail Mary (1985) set conversations ablaze. He was still intrigued by form, but his experiments took more popular expressions, and played on noir and crime aesthetics once more, Détective (1985) being another prime example.

While the 80s ended with Godard leaning into comedy, it also leaned into a certain return of his essayistic work, in particular, the beginning of what many consider his magnum opus Histoire(s) du cinéma. The 90s continued many trends set up in the 80s, but also saw him more self-reflective. He created an autoportrait, returned to the world of Alphaville and Lemmy Caution and as the 00s ticked in he played an older, reflective version of himself in Our Music (2003). At the same time, these were also the decades when he found himself making the remarkable Oh, Woe is Me (1993) and the colour-bending In Praise of Love (2001). There may be a slight increase in melancholy, but the eagerness to explore what cinema could be always remained.

It can only be described as beautiful to see how Godard lived on to experiment with the medium to the very end. His last three films, all released in the 2010s, showed incredible range and started conversations, granted, with Film socialism (2010) most were vocal annoyances with the so-called “Navajo English” used for the subtitles. His final grand accomplishment can today be seen to be Goodbye to Language (2014), which showed that a 3D movie with a talking dog could be something very different than what you can imagine, and once more showcasing his utter irreverence and humorous edge. I still hope I will get the opportunity to see it in 3D one day.

His final feature-length directorial effort, The Image Book (2018) also cemented his joy of discovery and eagerness to bring us something new. Nearing 90, he played with the proportions of the images and found how a glitch, created when an image readjusts to the screen, could be used as an intriguing new visual effect.

I would of course have wished for him to have created many more films, and the fact that he may have had two more films planned that he possibly just couldn’t do breaks my heart. I wonder what else he might have discovered or tried. His passion will however always live on, as will his eagerness, playfulness, inventiveness and humour. It is hard not to think of his films without smiling, and for that, we owe him a great debt.

My mind will continue to go back to the opening of Numéro deux, as well as the later scenes in the film where Godard is peering onto his footage, this time shown on two TV screens and remember that while the man is now gone, the images he created are still left with us.

Christoffer Odegarden is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of iCinema Magazine. He is also the host of the bi-weekly cinephile podcast Talking Images.