The 72nd Berlinale is set to kick off on the 10th of February, and it may reassure both attendees and casual observers to know that the event is very unlikely to get cancelled. This is an institution that not even Covid could rock. However, there is one film that did what an international pandemic could not do; it brought the Berlinale to a halt, ending in the cancellation of every single award. This is quite an achievement and only occurred once in the entirety of the festival’s 71-year history.

The fateful moment happened more than 50 years ago in 1970, and to make things particularly frustrating, this was the very year the Berlinale was celebrating its 20th edition. Was it really the work of a single film? That may depend on your point of view. However, one thing is clear, it all comes back to the controversy regarding one single film, the ironically titled o.k. by German director Michael Verhoeven.

Let’s look at how this now largely forgotten film managed to upset jury president and famed American director George Stevens (Giant, Shane) to the point that he had to have it excluded from the competition at all costs, and explore why you really should give it a look (hint: it is an exceptional piece of cinema).

Let’s delve into the film first, and then come back to why it was so terribly offensive to Stevens and most of his peers on the jury, as well as how their reactions led to the 20th Berlinale’s collapse and cancellation.

o.k. is Not Like Most Other War Films

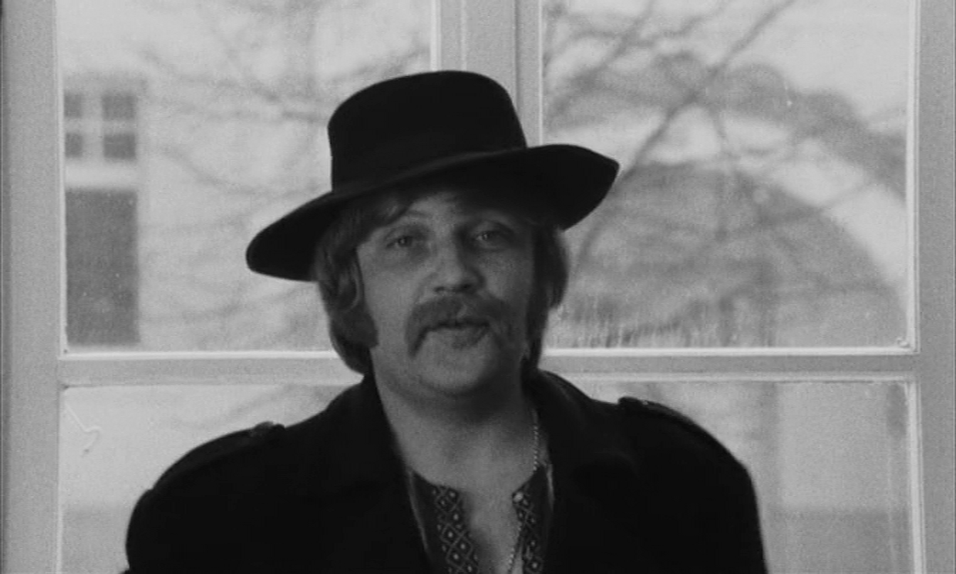

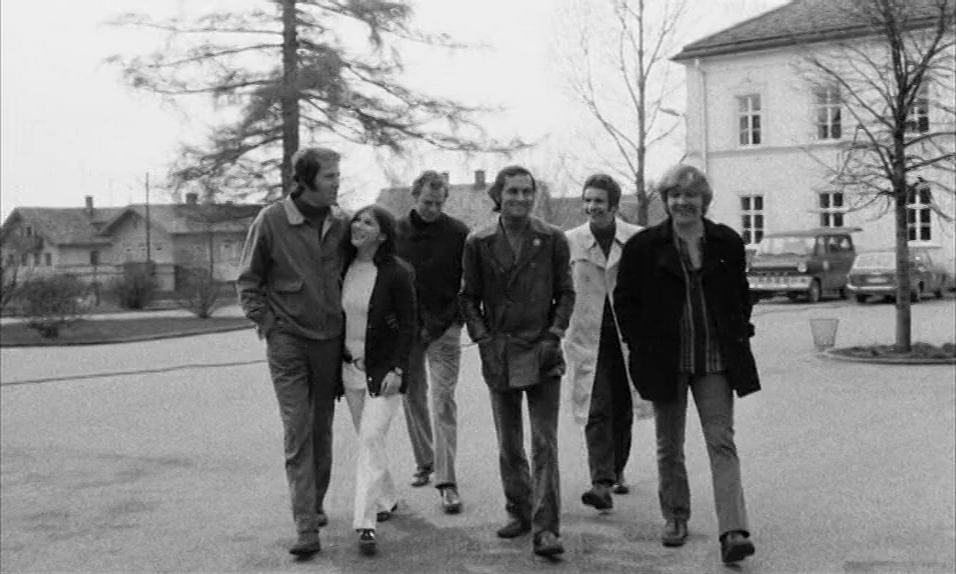

Opening with a powerful thrust, we follow five men as they walk through a gate, up a long driveway and enter a large building where workers are setting up video equipment. These five men are our lead actors and they are still not in character. Staff is waving them through the corridors, revealing the full operation before they meet up with the director in the costume room. We are about to begin.

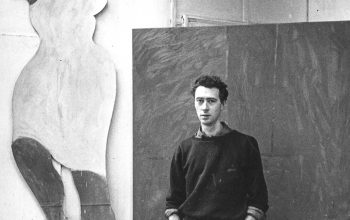

After getting into their respective outfits, US military uniforms to be exact, each actor gets time with the camera. One by one they give us a quick rundown of their name, profession, age, religion, military service and who they are playing. Interestingly none of the five men have had any military service and they do not necessarily look the part. Director Michael Verhoeven joins them as well, and lo and behold, he is the one person who has any connection to the German army, but then, it is not at all about them – or at least, only to the extent the film looks at abuses within the war.

We are about to witness a reproduction of a true story from the Vietnam War. A story that shocked and made waves across the world, though it would not be adopted onto the screen in the US until Casualties of War (1989). The horrific event was the rape of a young Vietnamese teenager by five US military men in 1966. Still fresh off the papers in the major 1969 exposé, o.k. serves up a take on the event that manages to be simultaneously dehumanizing and humanizing, abstracting and yet, in doing so becoming more universal. As a film, it is a cut with a blunt, rusty knife, coated with black humour that places us at a distance. It was created to confront and cause unease and it manages to do just that.

Verhoeven is never interested in creating a realistic representation of the Vietnam War, the Soldiers or the event itself. Vietnam here is represented by Bavaria and we are openly told this in the film’s early stages. Each of the actors, including Eva Mattes who plays the Young Vietnamese woman “Mao” are white Germans.

Even as our actors get into character it is very much clear that this is a performance of the events, and if you start to lose yourself in the film you will be it will be instantly smacked out of it by loud music and a title card introducing the next situation. In a way, it is a series of 2-3 minute episodes, with the title cards giving us a piece of information about what is to occur or a smug, and blunt comical reference undercutting it all.

Largely set in one location, the sparse outpost of the Soldiers, the film remains incredibly active, without a single moment of rest. The chapters certainly see to that. Chapter by chapter we learn to know the characters, and their relationship and see the event unfold. The performances are simultaneously stilted, yet in your face, with a lack of realism that somehow makes it all become more haunting. Unlike the reiteration in the Hollywood version, no one is spared. Even Erikssen, the one Soldier who refuses to participate, later portrayed by Michael J. Fox, stated almost coldly “Don’t worry Mao, I will report them”, rather than stepping in as she is brutally raped, knife to the throat.

The film is in many ways repulsive, or rather, it captures the repulsive, with the open and honest artificiality giving us some needed distance to make it a clearer conversation piece. Its coldness and bluntness give it near harrowing power as we see Brechtian techniques used in one of its most noble causes: forcing people to engage and think – and here of course, what we are to process and reflect upon is the Vietnamese war. In Michael Verhoeven’s film, war is not exciting or entertaining, it is repulsive, making o.k. one of the clearest anti-war films ever made, even with its very specific focus.

A monumental effort, deserving much analysis and reflection o.k. has faded out of the spotlight after its controversial release. This should change, as the film offers an opportunity to enter the zeitgeist of both the anti-war effort and the youthful cinema coming out of Germany at the very same time. o.k. is successful in both form and content and is arguably one of the purest (if not the purest) Brechtian experiments of German New Cinema, which is an incredible feat in and of itself. However, whereas many of the other Brechtian efforts of this movement, such as Schlöndorff’s brilliant Baal (1970 – itself based on a Brecht play), are mainly interested in the method for the power that arises from the style and form, o.k. uses it specifically to hit us with its messaging – while all the same delivering exceptional form.

It Was Perceived Anti-American Sentiments That Caused George Stevens’ Rage

In 1970 America was still actively engaged in the Vietnam war and the world was still in the middle of its Cold War with no end in sight. Tensions ran high! It may also help to be reminded that West Berlin was not inside West Germany, but an enclave inside East Germany. A film showing Americans negatively in such a time would certainly be controversial no matter what, and when you show American soldiers raping and killing a young Vietnamese woman you can probably see how tensions could rise.

While o.k. had been selected for the festival and allowed its premiere, seeing it became too much for Stevens. He immediately got behind excluding the film from the competition, meaning it could not receive any awards. Why? There are few sources confirming this, but according to DW.com it was because Stevens “refused to have a German accusing Americans of war crimes”. The fact that Stevens had been a U.S. soldier during the events of WW2 and helped liberate the Dachau concentration camp, may give you an indication of why he felt so strongly on the subject. This was still only 25 years after the end of the 2nd World War, and such sentiments were likely, not uncommon.

After a 7–2 vote from the jury, Stevens got his will pushed through and o.k. was excluded from the Berlinale.

Their justification cited the following guideline from the International Federation of Film Producers Associations: “All film festivals should contribute to better understanding between nations”. Roughly translated, this would mean that if the Berlinale festival were signalling that they were “o.k.” with such a film, by allowing it to compete, it would contribute to a worsening of understanding between nations.

Verhoeven himself disagreed not just with the decision to exclude his film, but the reasoning as well, stating: “I have not made an anti-American film. If I were an American, I would even say my film is pro‐American. The biggest part of the American people today is against the war in Vietnam”. His objection fell on deaf ears.

Everything Spiraled Out of Control

What Stevens and his peers seemingly thought would be a simple neutralization of a film he wished to distance himself and the festival from, soon caused a frenzy, even within his own ranks. Dusan Makavejev was one of the two dissenting votes, and he let his voice be heard, and loudly! Stevens on the other hand stayed silent in the media, as did most of the Jury, likely trying to ride out the storm. They generally declined comments and the only thing that slipped to the New York Times was that the committee “might reconsider”. Whether it simply became too late to change course is unclear, but the jury never altered its verdict.

The Berlinale itself puts much of the blame on the Jury, retrospectively stating: “the all too timid reaction on the part of the festival management fueled the conflict”. Regardless of your stance on this position, tensions certainly rose. The reaction from the participants was merciless. Director after director, producer after producer, decided to boycott the festival. Film after film started to be pulled from the lineup until there were very few titles left. In the end, the jury announced its resignation and the Berlinale was simply cancelled mid-way. A few films, those not withdrawn in solidarity, continued to be shown, but for all intents and purposes, it was over.

No Golden Bear, nor any other Berlinale awards were given out that year.

There were also further consequences. The director of the festival, Alfred Bauer, as well as the head of the umbrella organization Berliner Festspiele GmbH, Walther Schmiederer, announced their resignations. The future of the festival was in genuine question. After everything was said and done Alfred Bauer ended up staying as Festival Director, a position he held until he retired in 1976 and as we all know, Berlinale continued onwards without a single other cancellation. That being said, at the time things looked far more uncertain.

The Aftermath and a Happy Ending?

Opinions may very well be split on the events that happened and blame may be assigned differently. However, the fact that the Berlinale is still going strong more than 50 years later is something that will likely be celebrated by most. Rather than being crushed, the Berlinale rose once again after what happened and introduced reforms the following year. This included the founding of the International Forum of New Cinema, which aims to highlight brave new cinema.

But what about o.k. itself?

Interestingly West Germany was bold enough to make it their submission to the 43rd Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film category. It was obviously not selected, but it would have been interesting to see if a similar controversy had ensued there. Today, the film has been embraced by the festival to the point that o.k. was the closing film in the Forum Anniversary Programme in 2020, marking exactly 50 years since the event.

As for Michael Verhoeven, its director, he disappeared into obscurity for decades, mainly working on TV movies. Key exceptions to this are The White Rose (1982) and more importantly The Nasty Girl (1990). The latter not only swept the Berlinale, securing 3 awards, including Best Director exactly 20 years after he was excluded, but it was also officially nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards.

Despite this, Michael Verhoeven returned to making TV films and has minimal name recognition today. The same goes for o.k. and even The Nasty Girl. This is an absolute shame, as the techniques both films use to investigate war crimes and to encourage important conversations make them both cinematically and historically important. In the warm-up to the 72nd Berlinale, we, therefore, hope that you take the time to watch the one film that managed to upset their otherwise perfect continuity.

Christoffer Odegarden is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of iCinema Magazine. He is also the host of the bi-weekly cinephile podcast Talking Images.